Our program trains students to collect stories from local archives, community and national organizations, and our Harlem neighbors. We work with librarians and archivists to study these materials and share findings—via gallery exhibits, digital programs, and symposia. Our audience includes CCNY students and faculty, scholars from around the country and all over the world, and local residents of the Harlem community.

We are highlighting a few of the courses taught in our creative writing programs for MFA students and undergraduates. Listed briefly are the courses and a few selected projects that students have created.

Finding Central Asia in the Harlem Archives

by Aybike Ahmedi

Growing up in a small New Jersey town I felt caught between my three cultures: Uzbek, Turkish, and American. My siblings and I felt pressure from our parents and grandparents about our responsibility to preserve the Uzbek and Turkish cultures while navigating their fears of our generation’s assimilation to an American lifestyle. Most days I couldn’t decipher which parts of my identity fit and which parts felt forced, and my Uzbek history frequently felt far out of reach. I wondered what a pre-Soviet Uzbekistan might have been like because there is so little documented on Turkestan (Central Asia). Most of the available information is during the Soviet era and filled with propaganda. All that I had known and learned about Uzbekistan was through oral history; stories passed on through my grandparents and their friends that I continue to hold on to today while traversing this journey into my cultural identity.

What I never imagined was that I would come across parts of Central Asia’s hidden histories in the Harlem archives as I started my MFA in Creative Writing at The City College of New York in the Fall of 2021. A class in particular, which guided me to and allowed me to wade through these findings was, Evidence of Things Unseen: Art, Archives, & Harlem. Professor Gibbons who taught the class asked us to sort through The New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture’s archives of prominent figures from the Harlem Renaissance. It was through this research that I came across the Langston Hughes archives. I learned that Hughes traveled through Uzbekistan in the early 1930s about the same time that my great grandparents and their families were embarking on their departures from a Soviet occupied Uzbekistan. Swept by a surreal feeling of nostalgia for a place I have never visited, but had heard countless stories of through my childhood, I felt like I had stumbled across a treasure chest. I needed more. I wanted to know everything Hughes did there and if his experiences connected pieces of the knowledge I had on Uzbekistan or if his path had crossed ever so slightly with my ancestors’.

I was lucky to find that there was another Uzbek American who had come across these same archives, Zohra Saed. Zohra is a Brooklyn based writer hailing from the same Central Asian diaspora. She had been doing this research for years, which made it much easier for me to re-discover Hughes’s photos and journals. One key photo I would not have known about if it weren’t for her research was that of Langston Hughes and an Uzbek poet by the name of Karim Ahmedi. This one struck me because of the last name, Ahmedi, which is the same as mine. My family and I have never come across another with the exact spelling and pronunciation of our surname until now. This discovery hung over me for days bringing on dreams of what else I could possibly seek out through archival research. It didn’t take long for me to reach out to Zohra, who has been generous in sharing her work with me. We are both products of a large migration of the Central Asian diaspora. We are an immense diasporic group with very little documented in books or online throughout its history, making these findings vital in understanding our ancestry and building bridges that seemed unreachable for so long. Through this unwritten history Zohra and I were able to find a shared understanding of what our heritage means to us, and that at times words are not needed in grasping what another feels in their search for identity.

There is a magical component when mining the archives or utilizing them as muse. The research embeds itself into one’s soul and finds its way into one’s dreams. When the poet, David Mills, came to CCNY to read from his chapbook, Boneyarn, he explained the mystical dreams he had as he delved deeper into the archives of the thousands of enslaved African American mass graves that Manhattan was built over. The long forgotten African Americans he was researching came to him in dreams that at first, he could not make sense of. After confiding in a friend, he was encouraged that the ancestors were communicating to him through these dreams as he awoke their spirits in pursuit of telling their unheard stories. His friend told him, “They want you to tell their stories.” He expressed that many of the lines in his chapbook also formed in these dreams. Zohra had a similar experience when she was at the peak of sifting through Hughes’s archives at the Beinecke in Yale. When she first learned of Hughes’ friendship with poet Karim Ahmedi, Karim found her in her dreams and speaking in our native tongue told her, “Don’t forget me.” She was moved to go back and do further research although she had thought she had already found all that she could. She decided to search through documents incorrectly filed under Karen, which led her to find more on Karim Ahmedi.

Zohra recently invited me to moderate a panel where she presented her research and findings in the Langston Hughes archives of his time in Turkestan. I am grateful to her and the Silk Road Literary Festival for including me in this incredible experience. This panel was significant for me since I’ve spent most of my life ruminating over my ancestry, trying to find the truth of the journey of my lineage tracing back to Uzbekistan. It was not always easy to map out the routes and roads both my paternal and maternal great grandparents took as they left their homeland, which they were forced to flee due to the rise of oppression from the Soviet Union. My family lived in various countries along the voyage from Central Asia, like Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia, before finally settling in Turkey in the 1960s where both my parents were born and where many of my relatives continue to live today.

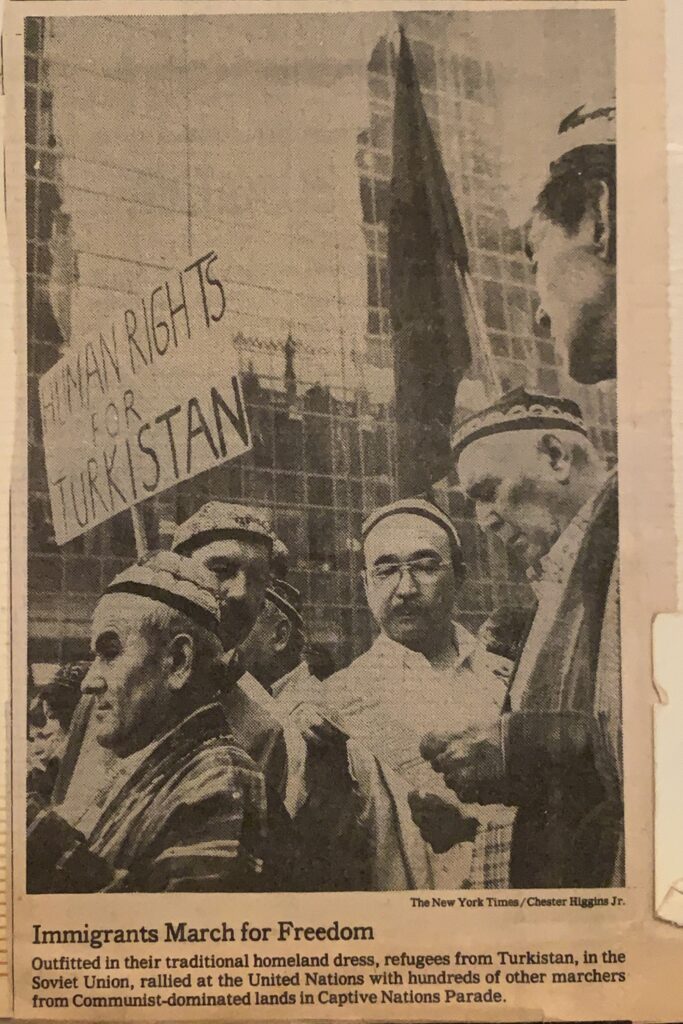

My father’s family migrated to the United States in the early 1970s along with a large group of other Uzbeks, where my grandfather and his friends founded the Turkestan American Association. This organization was created to preserve our heritage and keep us united in a land far from home. Today, I am working on my own oral history documentary capturing the oral stories of the remaining elders in our Uzbek community as they give shape to our diaspora. I am also documenting The Turkestan American Associations photos, events, and experiences over the years into an archival library to fit a small part of the puzzle of our great Central Asian diaspora, so that our history will not be lost forever. Perhaps one day this film and photos will find a home in the archives expanding on the gaps in Uzbekistan’s documented history.

My time in the MFA in Creative Writing Program at CCNY and working as an Archival Assistant to Professor Gibbons has enlightened me to the value of archives, and how worlds and heritages can connect in the most unexpected places. Langston Hughes and his friends led the Harlem Renaissance, a vital part of American history and culture. It was a community they formed to unite African American migrants who are also part of a larger diaspora. Through the archives you can see that not only Hughes, but other members of the Harlem Renaissance have also traveled to Central Asia. Seeing my current world in parallel to my lineage and the way they blend and make sense of one another has been one of the most exciting journeys I have undertaken. Whether it has been by chance or a path my ancestors have opened for me, I am filled with gratitude that I have found my way to The City College of New York as well as the archives. Archival research has opened many doors for me, and I know it will continue to do so.

Bio: Aybike Ahmedi is an Uzbek, Turkish, Muslim American writer from New Jersey. She explores her Central Asian heritage through her oral history projects and is currently writing and filming a documentary on the Central Asian diaspora. Her writing has appeared in the Cephalopress anthology, Borders and Belonging. She teaches English Composition at The City College of New York where she received her MFA in Creative Writing.

The Harlem Lynching Tree, with Poems for Alma

by Taylor Alexis Baker

CCNY MFA COURSES USING ARCHIVES AS MUSE

The Evidence of Things Unseen: Art, Archives, and Harlem

Professor William Gibbons

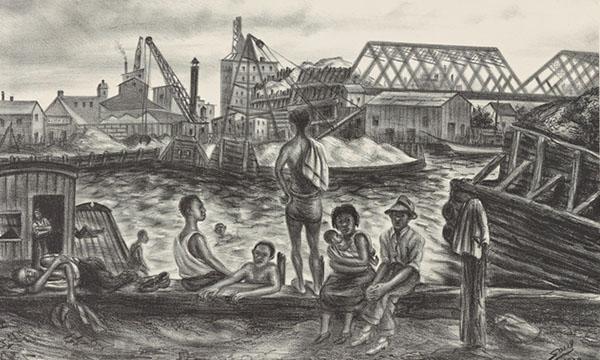

The years between the collapse of Reconstruction and the end of World War I mark a pivotal moment in African American cultural production. Christened the “Post-Bellum-Pre-Harlem” era by the novelist Charles Chesnutt, these years look back to the antislavery movement and forward to the artistic output and racial self-consciousness of the Harlem Renaissance as “past is prologue.”

The Evidence of Things Unseen: Art, Archives, and Harlem examines the political, cultural, and social forces that influenced and defined the Harlem Renaissance. In addition to class discussions of assigned readings, the course functions as a research workshop, providing support for primary research and exposing students to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture to get hands-on experience accessing and utilizing archival collections and digitally publishing their findings.

Student Projects:

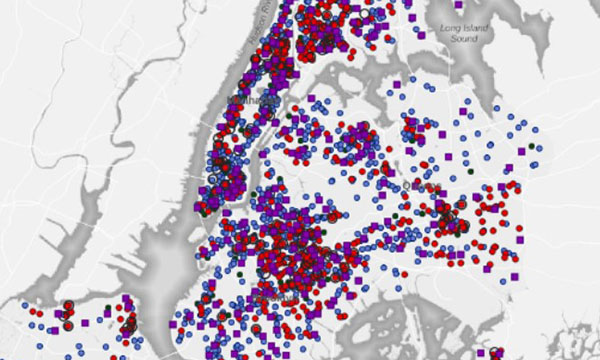

Gentrification & the Cultural Identity of Harlem

A Freshman Inquiry writing Seminar (FIQWS)

Professor William Gibbons

This course explores contemporary Harlem, which is at a crossroads. After three centuries and five decades of continuous. Students position themselves as community activists engaged with libraries and archives, community boards, non-profits, and city and state agencies with an aim toward creating useful resources that can inform public policy to achieve affordable housing and sustainable equitable economic and community development for both longtime residents, businesses and newcomers. development, Harlem is poised for a rebirth.

Student Projects:

Undergraduate: Fall 2019

Telling Rivers: Annotating and Writing with Artifacts

Professor Nelly A. Rosario

Telling Rivers: Annotating and Writing with Artifacts is an archival storytelling project based on the autobiographies of Langston Hughes, The Big Sea and I Wonder as I Wonder. This project comprises two collections of artifacts related to each work, as well as a selection of inspired writings. The contributors were students in Knowing Rivers (ENGL B2031, Fall 2020), an MFA Program writing workshop and critical-practice course centered around the Langston Hughes Festival Archives at City College.

Student Projects:

by Willette Francis

by Isabela Cordero

by Jacob Kose

by Students of ENGL B2031

Taste of the Archive: African American Literature and Oral History as Praxis

by Janée Moses

This seminar, which begins and ends with Brent Hayes Edwards’s essay, “The Taste of the Archive” bends genre with a simultaneous study of narrative, oral history, and archive to highlight aspects of the past that are “hard to pin down” or elusive. In the first part of the course, students will explore fiction and non-fiction texts in the African American literary canon that deal with issues of race, class, gender, sexuality, and belonging to highlight contradictory truths that “can’t quite be explained away,” and consider how methods of African American literature can be applied to narrative-based oral history projects that embrace, rather than bridle, complicated truths about our shared pasts.

In the second part of the course, students will merge African American literary methods, archival practices, and oral history methods and theory to create their oral history projects. These projects will include the development of oral narratives that move from the realm of spoken word to polished manuscripts. In addition to the manuscript, students will analyze their oral history practice by writing methodology statements that expand the field of oral history.

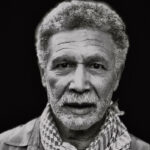

Professor Gordon Thompson has a laudable career spanning nearly 24 years of teaching and service at City College, Louisiana State University, and Stanford University. As director of the Black Studies Program, he had a record of administrative leadership, including planning, budgeting for and managing an academic program. As creator, principal investigator, and director of the RAP-SI project of the Black Male Initiative, he demonstrated the ability to successfully organize a staff and build a service-oriented mentoring program. As director of the Langston Hughes Festival Committee, he has been in continuous service to the Committee since 1990. As professor of African American and American literature in the English Department he has demonstrated a strong publication record with scholarly expertise in the area of the African American narrative praxis. Lastly, as a scholar, he has several peer-reviewed publications, is a frequent participant at national and international conferences and is the editor/co-editor of several books.

Professor Gordon Thompson has a laudable career spanning nearly 24 years of teaching and service at City College, Louisiana State University, and Stanford University. As director of the Black Studies Program, he had a record of administrative leadership, including planning, budgeting for and managing an academic program. As creator, principal investigator, and director of the RAP-SI project of the Black Male Initiative, he demonstrated the ability to successfully organize a staff and build a service-oriented mentoring program. As director of the Langston Hughes Festival Committee, he has been in continuous service to the Committee since 1990. As professor of African American and American literature in the English Department he has demonstrated a strong publication record with scholarly expertise in the area of the African American narrative praxis. Lastly, as a scholar, he has several peer-reviewed publications, is a frequent participant at national and international conferences and is the editor/co-editor of several books. Emily Raboteau

Emily Raboteau Dr. Vanessa K. Valdés is the director of the Black Studies Program at The City College of New York-CUNY. A graduate of Yale and Vanderbi

Dr. Vanessa K. Valdés is the director of the Black Studies Program at The City College of New York-CUNY. A graduate of Yale and Vanderbi

Sydney Valerio believes we are all a living archive of the stories and places our bodies navigate. As a creative, she is fueled by her professional work as an educator and community cultural worker to create spaces and experiences for all parts of the community to engage with and access.

Sydney Valerio believes we are all a living archive of the stories and places our bodies navigate. As a creative, she is fueled by her professional work as an educator and community cultural worker to create spaces and experiences for all parts of the community to engage with and access.